Three Lessons in Ethical Leadership from Africa

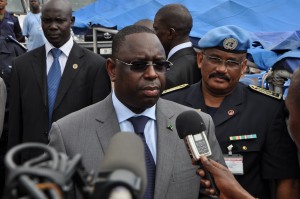

The date is March 25, 2012. After a night of tension in a nation hailed for its democratic credentials, Senegal’s third president Abdulaye Wade, telephoned his opponent, Macky Sall, to concede defeat after a bitterly fought election that had gone into the second round. The West African nation breathed a collective sigh of relief following months of unrest marked by deadly clashes between opposition activists and police.

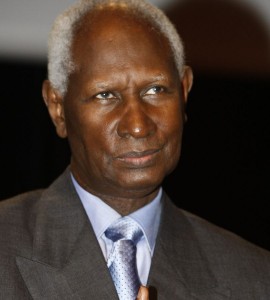

Abdoulaye Wade

Wade’s attempt to change the constitution to contest a third term was at the root of the crisis. For over 6 months, more than 200 civil society organizations under the umbrella group, M23, organized daily nationwide protests to force Wade to reverse his declared bid. When Wade was elected in 2000 for a seven year mandate, Senegal had no term limits. He was re-elected in 2007 after introducing a two-term limit and reducing the mandate to five years but he changed his mind during the final months of his presidency, prompting fears that Senegal, long considered an exemplar of democracy, was on a dangerous precipice. On the eve of the vote, in the aftermath of rioting that led to the deaths of protesters and police, one protest leader said: “This is an appeal, a solemn, strong, and resolute appeal to engage in resistance. We are ready to bear any cost and prepared to make any sacrifice.”

Macky Sall

The level of distrust was palpable. Opposition activists deployed observers in all 11,000 polling stations who texted voting counts to their own collation center in the capital Dakar using independent communication links from a server outside the country. What many didn’t know was that back in the presidential palace senior military officers approached Wade as votes were being counted and told him that their own private surveys indicated that the president had lost the poll. Crucially, they also told him that if he clung to power he should not expect the support of the Senegalese armed forces. The officers were quick to add that the seizure of power by the military to avert a possible vacuum was also out of the question. What they desired was for the poll results to be respected and the constitution to be upheld. Seeing no viable alternate options, Wade telephoned Sall to congratulate him on his victory.

The centrality of ethical leadership for advancing security in Africa is a key theme of the “Next Generation of African Security Sector Leaders” program currently being conducted by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies for 48 up-and-coming African security professionals. Civil military relations and the upholding of constitutional requirements are key dimensions of such ethical dilemmas and the leadership required.

» Read also: Africa’s Strategic Future: The Consequence of Ethical Leadership

Abdou Diouf

Twelve years earlier, similar events transpired in Dakar. Wade, then an opposition leader, had forced his predecessor, Abdou Diouf, into a second round in a poll that was every bit as bitter and contested as the one he lost in 2012. On the night of the March 19, 2000 run-off, Diouf retreated to his private study at the presidential palace. An aide sitting outside the leader’s office revealed that as results poured in the mood at the palace became like a funeral. “It was extremely traumatizing, no one said anything … all the stations were repeating the same results … until 3 in the morning the president went over the results again and again.” At some point senior government officials close to the president urged him to stop the counting process and declare himself the winner or invalidate the election as it was clear he was losing. Senior military officers present in the meeting told their commander in chief that if he went along with this advice, he would not have the military to back him up. They also added that a military coup on his behalf would not be entertained by the Senegalese armed forces. Diouf, to preempt the issue, called Wade at dawn to congratulate him and concede defeat, something that Wade went on to do when faced with a similar decision years later.

* * *

Henry Odillo

On April 5, 2012, a dangerous turn of events was transpiring in Malawi after the cabinet had failed to inform the public of the death of sitting president Bingu wa Mutharika. Political leaders jockeyed for power in moves that some allege were designed to prevent then Vice President, Joyce Banda, from taking over as required by the constitution. Amid the extremely volatile situation that unfolded over the next several days, then foreign minister and brother to the late president Peter Mutharika (now president) reportedly asked the military to take over to avert a power vacuum. The army commander, General Henry Odillo, is said to have refused, stating that the Malawian defense forces were sworn to protect constitutional order and would not inflame the already tense situation by seizing power.

Another major test for the Malawian military came on May, 24 2014. Then, incumbent Joyce Banda nullified the results of a hotly contested election citing “irregularities” and promising a new poll that she would not contest. The decision triggered massive protests and a challenge from the national electoral authority as well as the national assembly. Rumors began to spread that the military was maneuvering to seize power to avert crisis. General Odillo wasted no time issuing a strongly worded statement dispelling the rumors, affirming support for constitutional principles and placing the army under strict orders, to “remain in the barracks and give space for the politicians to resolve the impasse.”

* * *

In South Africa in 1990, a new nation was struggling to be born. Despite the release of political prisoners and the unbanning of the African National Congress (ANC), oppressive laws remained in place. Clashes between the ANC’s military force, Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation) and security forces of the apartheid government were commonplace. Unrest in the townships had boiled over and many gruesome massacres, which the ANC blamed on what it called “a sinister third force,” had gripped the country in fear. On the night of August 7, after a 14 hour meeting in Pretoria between the ANC’s senior leadership and government counterparts, Nelson Mandela announced the suspension of armed struggle to pave way for formal negotiations on a new constitution.

Several miles away in the Transkei, Chief of Staff and Commander of Umkhonto we Sizwe, the charismatic Chris Hani, was facing a serious moral and ethical dilemma: whether to obey, or refuse, the orders handed down to him by his Commander in Chief, Nelson Mandela. In an undated video interview that went viral several years after his death, Chris Hani speaks his mind:

I want to be honest … I was annoyed. I was marooned in the Transkei when this decision was announced by the government of the day. I spent more than 27 years in Umkhonto We Sizwe … I commanded scores of young people who died in combat … I know their names and faces … they put everything aside to enlist in our army and fight for our country. I didn’t sleep when our delegation was locked in negotiations and when the decision came, I felt like crying. I was deeply bitter that it had been taken without consultation with those of us who were involved in the physical side of the struggle. But as a disciplined soldier I accepted it. When it was later explained to me that this was important to maintain the momentum of negotiations, I accepted to be reined in.

Chris Hani

With this decision, Hani, second in popularity only to Mandela, and still considered by many to have been his heir apparent, put his full backing behind the closure of the ANC’s military camps across the African continent. Military formations were broken up, weapons were returned to the governments that provided them, infiltration routes into South Africa were closed, and thousands of fighters were repatriated to South Africa for decommissioning and cantonment. Then, on April 10, 1993, Chris Hani was gunned down by a white ultranationalist in front of his house. Mandela explains that if there was any moment when full scale civil war would erupt in South Africa, this was it. With decommissioned ANC soldiers organizing to resume the armed struggle, youths pouring out of South Africa’s townships demanding revenge, and Mandela’s peers now questioning the decision to suspend military activity, the ANC leader appealed for calm.

According to Hani’s close friend and fellow combatant, Tokyo Sexwale (now a cabinet minister), Mandela centered his address on Hani’s dream for a democratic South Africa, imploring combatants to keep this dream alive by refraining from war. “As he made his appeal we saw Mandela transition from a party leader to a statesman,” explained Sexwale.

“De Klerk could not have stopped what was to come … it was Mandela, our President, talking to his people.” Sexwale noted that shortly after the appeal the ANC and the apartheid government agreed to a date for the first multi-racial, democratic elections. “It should be forever remembered that the date for our national elections was set as a result of Hani’s death.” Across the country ANC commanders who once served under Hani reined in combatants with the same vigor that Hani himself displayed when he obeyed Mandela’s order to disarm three years earlier. This was significant because military integration had not yet begun and the ANC’s Military High Command still exercised command and control over several brigades earmarked for integration.

* * *

These three examples, taken from different contexts and periods, carry noteworthy lessons in ethical leadership for the continent’s next generation of military leaders. In Senegal and Malawi, the military establishment had the opportunity to seize power but was restrained by institutional norms and the strong personal commitment to those norms by military leaders. This is instructive because these two nations have never experienced military coups. Senegalese Air Force Chief of Staff, General Biram Diop, attributes the professional conduct of the Senegalese military officers to the following:

These three examples, taken from different contexts and periods, carry noteworthy lessons in ethical leadership for the continent’s next generation of military leaders. In Senegal and Malawi, the military establishment had the opportunity to seize power but was restrained by institutional norms and the strong personal commitment to those norms by military leaders. This is instructive because these two nations have never experienced military coups. Senegalese Air Force Chief of Staff, General Biram Diop, attributes the professional conduct of the Senegalese military officers to the following:

- High quality of both civilian and military leadership

- Implementation of the Armée-Nation concept and other measures to inculcate and institutionalize civil military relations

- Assignment of the military to a constructive role in supporting civil authorities with engineering expertise, medical and humanitarian assistance, and, vaccination campaigns

- Heavy emphasis on professional military education and norm-modelling at all levels of leadership and command

- Regular exposure and participation in international peacekeeping missions

In the Malawian case, strong and decisive leadership by the army commander stamped out any doubt that might have existed in the military establishment about intervening. Had politicians succeeded in preventing Joyce Banda from succeeding Mutharika, it would not have been through means of a military coup. This is a testimony to the discipline of the Malawian armed forces.

In the South African case, a climate of uncertainty clouded the political process. On one side stood the apartheid government which lacked legitimacy but controlled a powerful military and other instruments of coercion. On the other was the ANC, trade unions, and pressure groups that did not have access to state resources but commanded significant coercive power in the form of thousands of militarily trained and angry youth whose acceptance of authority was by no means guaranteed according to ANC icon (now cabinet minister) Mac Maharaj. Many viewed armed struggle as leverage that could be used to force concessions. The decision to suspend it was risky and because it was done without consultation there was no guarantee that the tremendously popular Hani would obey Mandela’s orders. It all came down to an ethical decision.

ANC military historian, Janet Cherry, explains that the ANC traditions required the subordination of Umkhonto We Sizwe to political direction. Hani and others were raised and trained in this tradition. Military leaders were also trained to think strategically and many like Hani concurrently held top positions in the ANC. Hani’s decision to implement Mandela’s order is therefore noteworthy. Mandela called him “one of the greatest leaders the country had ever seen.” The example he set in ethical leadership, in turn, was followed by his peers when Mandela appealed to them to stand down in honor of their slain hero and navigate their country from the brink of civil war.

Related Africa Center Resources

- “Effective Leadership in Africa’s Security Sector,” presentation by General (ret.) Martin Luther Agwai, Former Chief of Defense Staff, Nigeria, at the Next Generation of African Security Sector Leaders Program, October 23, 2015.

- Emile Ouédraogo, “Advancing Military Professionalism in Africa,” ACSS Research Paper No. 6, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, July 2014.

- “Leadership efficace dans le secteur de la Sécurité en Afrique,” presentation by General Lamine Cisse, Former Army Chief of Staff of the Senegalese Armed Forces at the Next Generation of African Security Sector Leaders Program, October 22, 2014.

- “Military Professionalism in Africa,” interview with Emile Ouédraogo, Retired Colonel, Burkina Faso Armed Forces, September 9, 2015.

- “Ethical Principles for Leadership,” presentation by Joseph J. Thomas, former Director of the John A. Lejeune Leadership Institute, Marine Corps University, at the Next Generation of African Security Sector Leaders Program, October 23, 2014.

Additional Resources

- Biram Diop, “Civil-Military Relations in Senegal,” Best Practices Manual, Council for a Community of Democracies, 2011.

- Abel Esterhuyse, “The Leadership Factor in South African Military Culture,” Defense Studies, Volume 13, No. 2, March 2013.

- Raymond Suttner, “Culture of the African National Congress: Imprint of Exile Experiences,” Journal of Contemporary African Studies, May 2013.

- “The Elders Debate Ethical Leadership,” Al Jazeera debate with Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Kofi Annan, Gro Harlem Brundtland, and Hina Jilani, November 6, 2013.

- “Leaders: Nelson Mandela,” Africa Vision interview with Former South African President, Nelson Mandela, July 1996.

- Raymond Suttner, “The African National Congress (ANC) Underground: From the M-Plan to Rivonia,” South African Historical Journal, Volume 41, Issue 1, 2003.

More on: Leadership Malawi Military Professionalism Senegal South Africa